Learn From The Masters: Walker Evans

Last time I, showed you the photographs of Joel Sternfeld. A photographer who’s work influenced mine a lot. But even Joel Sternfeld followed in the footsteps of other artists and one of them is Walker Evans who started the documentary tradition in American photography.

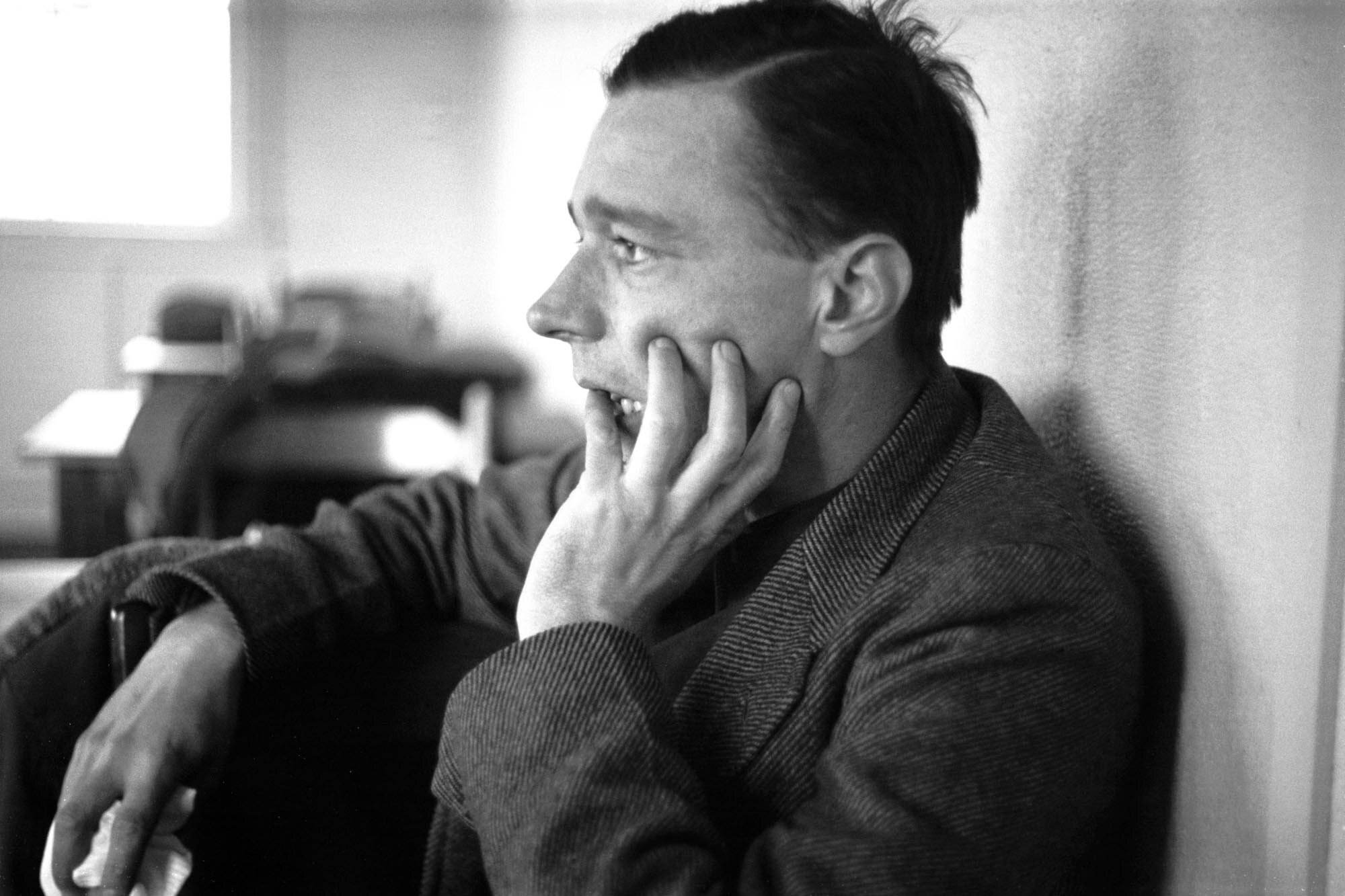

Walker Evans in 1937.

He loved photographing the vernacular—people found along the road, in the streets of small towns, or in cafes. For fifty years, he captured roadside America and he still is an inspiration for dozens of today’s photographers. Even more than Sternfeld’s work, his photographs read like literature and the work better in a series than separately but there’s a problem...

Related • Little Things That Inspire my Photography: Motel Rooms

Exploitative photography?

Yes, his photos are great—simple and elegant compositions, a clear style and expressive portraits. But that’s not why I want to put Walker Evans into this list of photographers who inspire me. There’s a problem that intrigues me. It’s problem a lot of photographers struggle or have to deal with and it’s the subject.

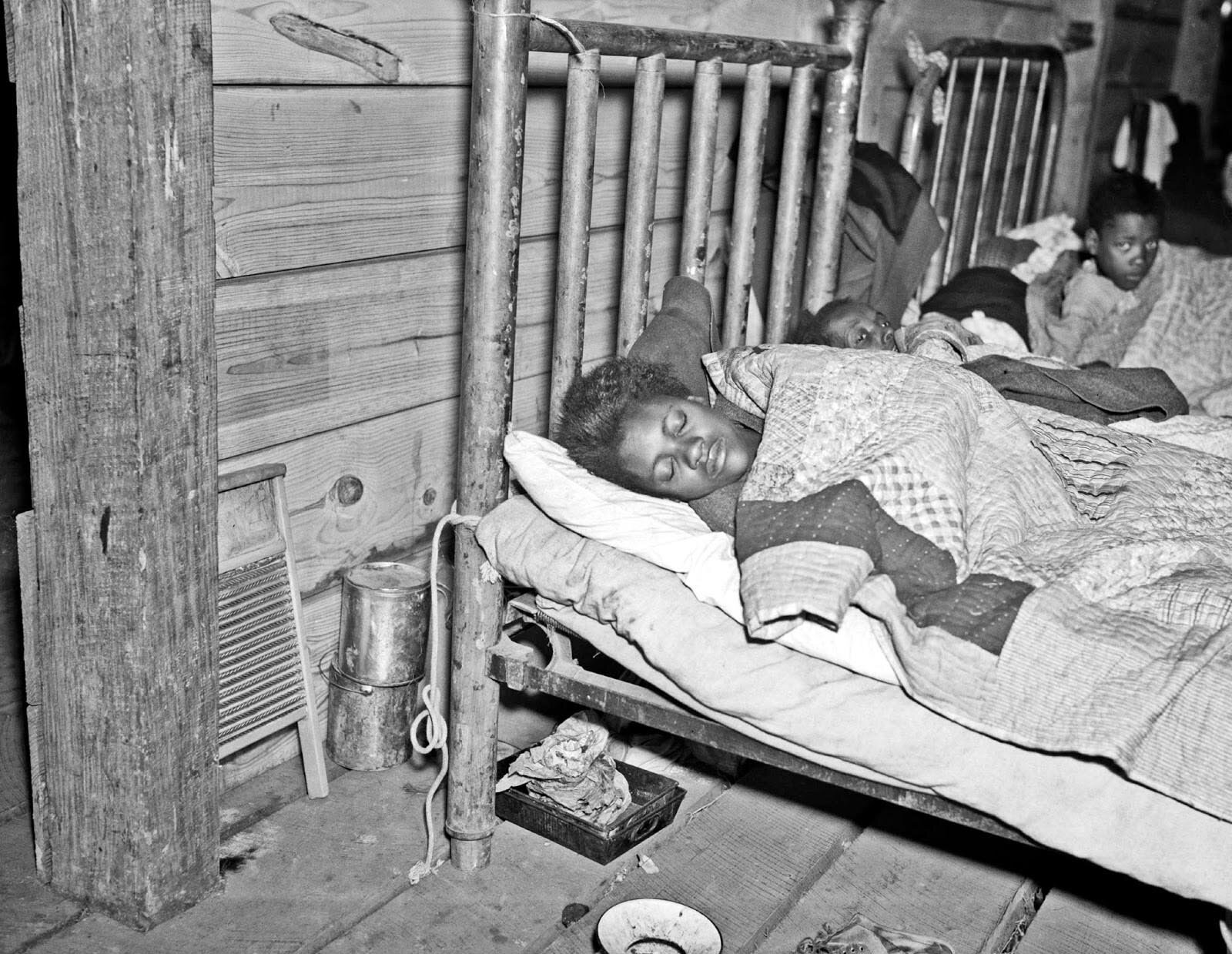

Alabama, 1936. © Walker Evans

Walker Evans documented the vernacular for years but his own life was very different from the subjects he photographed who were mostly poor rural farmers. He was born into an wealthy family so he didn’t identify with his subjects.

I have been lucky in my life too until now: Higher middle class family, good education, job opportunities. I’m not complaining about anything. I've been traveling the world for almost a year already for f*ck’s sake! And that’s where the problem I want to talk about lies.

Just like Walker Evans, I’ve photographed people all over the world who are struggling, whether for assignments or personal work. Some of those people only allow me to take their photo in return for money. I always refuse but in the end, I’m looking to get paid for my work—for the photographs I create… Am I—are we photographers—exposing truth or exploiting the powerless?

Alabama, 1936. © Walker Evans

Personal work vs assignments

In a way, working as a photojournalist and capturing people in need or suffering is justifiable. You’re letting the world know about what’s happening you get paid for it. But what about photographers like Walker Evans and other documentary photographers who try to find those people to photograph them for personal projects?

They don’t start a project to bury it somewhere on a hard drive or in an archive. The want people to see it and—even better—get something out of it. We all need to pay the bills, right? For my series ‘Behind the Redwood Curtain’, I also spent three weeks photographing an area in an economic downfall because it intrigued me. When it was finished, I wanted people to see it and I wanted it to get published in magazines.

Red Cross infirmary, Arkansas, 1937. © Walker Evans

Why are photographers and documentarians so interested in those subjects? Can you call it art or should we look at that kind of documentary photography differently out of respect for the people depicted? Is it OK to refuse to pay people for a photo but afterwards try and get similar photos published in magazines?

I always try to photograph people with respect and I think there’s nothing wrong with it. Photographers and film makers have always been interested in what’s different or unique—either because they want to learn about it or because the want to let other people know about. And on the other side, people have always been interested in watching and discovering those unique subjects.

I think it’s fine but I still wanted to write it down here. I have struggled with the same questions a few times while photographing dying children in Africa or struggling people anywhere in the world. This problem is as simple as it is complex. What do you think about?

What I’ve learned from Walker Evans

So, in every episode of “Learn from the Masters” I try to select one of my photos where you can see that I’ve learned from or have been inspired by the photographer whom I’m talking about. In the case of Walker Evans, I have to go for the portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs.

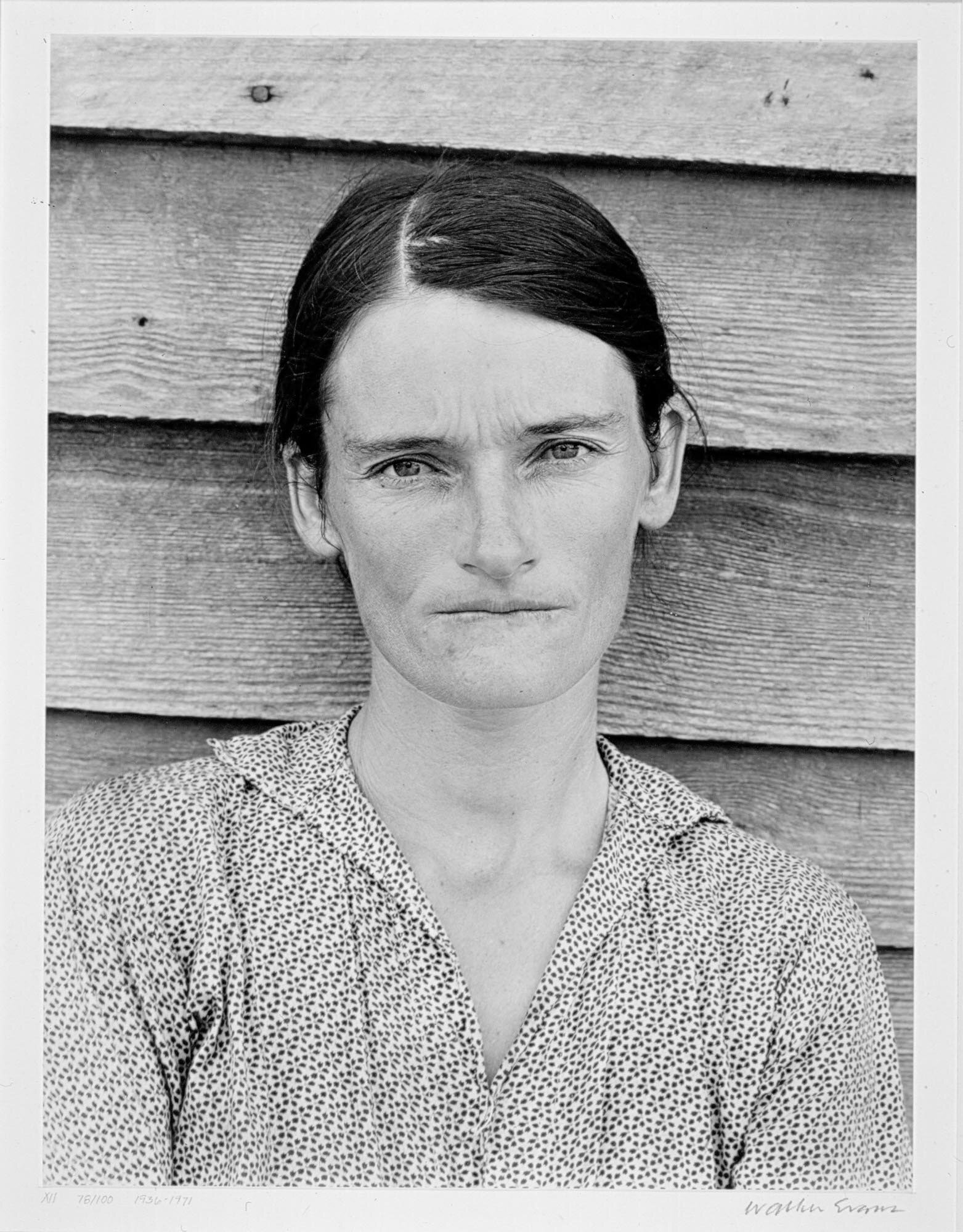

Allie Mae Burroughs, 1935. © Walker Evans

A portrait from my series “Behind the Redwood Curtain”.

That intense gaze and the slight frown. It’s a really strong portrait because in a way, you don’t really know how she’s feeling or what she’s thinking but you get a sense of who she is. Whenever I make a portrait, I want to capture the same. I want the viewer to get a sense of who the person in the photo is while still maintaining some mystery.

Books by Walker Evans

The photos shown in American Photographs are shot with different types of film and different cameras. They have different crops and show an array of different subjects. American Photographs shows what America was and is—a collection of cultures, people and places. That’s also how his photos are best viewed, as a collection in a book or exhibition.

The book Walker Evans showcases his most iconic images celebrating his fifty year career. Again, a collection of images depicting everyday life in America, in both urban and rural settings.

“Photographing in New England or Louisiana, watching a Cuban political funeral or a Mississippi flood, working cautiously so as to disturb nothing in the normal atmosphere of the average place, can be considered a kind of disembodied, burrowing eye, a conspirator against time and its hammers.”

Biography

Walker Evans was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on November 3, 1903. The family settled in Kenilworth, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, where his father worked in an advertising firm. Walker attended several private schools with the ambition to become a writer but dropped out of college after his freshman year.

In 1926, Evans moved to Paris, looking to become a writer riding the artistical and intellectual wave of avant-garde postwar Europe. He failed miserably.

“I wanted so much to write that I couldn’t write a word.”

In 1928, then he came went back to the United States, he turned to photography. He looked for something more than the aesthetic or the commercial aspects of photography. He aimed for stories beyond the literal or the artistic.

During the early years of his career he had many jobs in New York City, where he became friends with several distinguished writers to be. Evans worked with the critic Lincoln Kirstein in 1931 and he published some of Evans' work in an avant-garde magazine.

New York, 1938. © Walker Evans

Evans’ first exhibition was at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1932. In the following year, many of his pictures were used to illustrate social conditions in Cuba. In the mid-to-late 1930s, Evans worked with a group of sociologists and photographers in a study of poverty in the United States during the Great Depression. It was the most successful time of his life.

The quality of Evans' work gained wide recognition in 1938 with an exhibition in New York City's Museum of Modern Art and publication of American Photographs, an important book on the history of photography.

On leave from FSA in 1936 Evans collaborated with James Agee on assignment from Fortune magazine in a study of the life of Southern sharecroppers. From 1945 until 1965 Evans was an editor of Fortune, and from 1965 until his death in 1975, he taught a course at Yale University.